Cody Marshall remembers when the bulldozers first showed up to tear down the sprawling barracks-style housing development he’d lived in his whole life. It was 2013, and the Iberville development, which stretched for blocks on the lake side of the French Quarter, was the last of the city’s original public housing complexes still standing.

Now, six years later, Marshall is back living in a redeveloped neighborhood that he helped design. Gone are the Iberville’s rundown red brick buildings, barren courtyards and concrete stoops. In their place are colorful townhomes, coffee shops and freshly paved streets.

“All I know is, it changed for the better,” said Marshall, 38.

Like Marshall, thousands of New Orleans residents who grew up in huge government-subsidized housing complexes built in the mid-20th century have seen their former neighborhoods entirely remade. The transformation began in 2000, when the St. Thomas complex was torn down to make way for the mixed-income development called River Garden.

Then in 2007, after Hurricane Katrina laid waste to much of the city, government officials made the difficult call to largely raze the “Big Four” complexes — C.J. Peete (formerly Magnolia), Lafitte, St. Bernard and B.W. Cooper (formerly Calliope) — and build mixed-income neighborhoods in their place.

That left the Iberville, long derided by many who felt it hindered development on several nearby blocks of Canal Street. That replacement finally got traction in 2011 and was declared substantially complete on Wednesday.

Combined, the redevelopments comprise the most radical change to the city’s urban landscape since the storm.

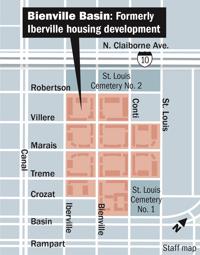

Now called Bienville Basin, the Iberville project was one of the first of its kind to receive funding from an Obama-era federal program called the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative, which aims not only to rehab distressed public housing complexes but also to spur development in the neighborhoods that surround them.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development program also works to connect public housing residents to jobs and workforce training.

The developer, HRI Properties, and the Housing Authority of New Orleans say Bienville Basin has achieved those goals, and that reinvestment in the neighborhood is happening.

“I don’t know if Tulane would be as excited about investing in that neighborhood (around the former Charity Hospital a few blocks away), but for what we did,” said Tom Leonhard, president and CEO of HRI Properties. “What we have always said is, “This is more than just a housing development. This is an economic development investment in the state.’”

Reimagining the Iberville

Built in 1941 over the demolished former Storyville prostitution district, the 23-acre Iberville was one of two housing developments in New Orleans opened exclusively for white residents.

The “super block” its buildings sat on was designed not to face the surrounding community, a decision that would be criticized in later years for contributing to crime and isolating poverty.

By the early 1950s, police were being called to deal with gang members who were damaging property and robbing people who wandered near the complex. Many of the culprits weren’t from the neighborhood, but they took cover in its alleyways and courtyards.

The scene was largely the same when African-Americans began trickling into the Iberville in 1965. Whites, many unwilling to accept desegregation, fled the project with the help of low-cost loans and jobs. The area was exclusively black within a decade, according to news accounts.

Problems worsened as the crack cocaine epidemic of the early 1980s and ’90s wreaked havoc on the Iberville and other poor communities.

All of it led to various redevelopment proposals to tear down what was seen as a problem housing development. Former Saints owner Tom Benson proposed building a stadium atop the site; a consultant hired by Mayor Sidney Barthelemy wanted to raze it and other housing complexes altogether.

Those plans were denounced by Iberville residents who accused developers of trying to wipe them out.

Fast-forward several decades, and seeing an opportunity to secure federal funding to remake the Iberville area, officials with HANO, the city, HRI and the nonprofit Urban Strategies began lining up support from residents for a total refashioning of the area.

The feds eventually granted the city $30.5 million under the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative — just a portion of the $600 million in government and private money that it took to build Bienville Basin.

To avoid repeating the pattern of clustering the poor in one area, HUD required that the money be spent on mixed-income complexes that would serve both middle- and low-income residents.

While that was also the goal of HUD’s HOPE VI program, the federal initiative that helped transform the city’s other housing developments, that program did not work to improve the surrounding neighborhoods.

It also did not require HANO to replace each low-income housing unit it demolished, in order to ensure that poor residents weren’t scattered to developments and homes far from the neighborhoods where they once lived.

“What is very different in Choice Neighborhoods is … instead of focusing on the redevelopment of the public housing site itself, it’s more of a holistic approach, a whole neighborhood revitalization,” said Josh Collen, president of HRI’s Communities Division.

Getting public input

Past unsuccessful attempts to revamp Iberville, and the furor that followed the City Council’s 2007 vote to tear down the city’s four original projects for black residents, prompted officials to reach out to Iberville’s tenants early in the planning process.

The transformation of the “Big Four” into Harmony Oaks, Faubourg Lafitte, Columbia Parc and Marrero Commons largely excluded residents from decision-making and displaced them to far-flung parts of the city, critics charged.

So, even before the grant application was submitted, a team of seven residents elected by their neighbors aided architects in creating a plan for the new complex in the Iberville area.

Those residents, Marshall included, were paid for their work.

“You’ve got to include the people that live there, which is what we did,” said April Kennedy, HANO’s special programs administrator. “People have made some serious mistakes when they make some assumptions.”

The original site’s basic design was one of the first things to go. Instead of “something that separated families from the surrounding neighborhoods,” the new townhomes and multifamily buildings were built to face the street, said Ellen Lee, the city’s director of community and economic development.

HUD also required HANO to provide a one-for-one replacement of more than 821 deeply affordable Iberville units, about half of which were occupied when demolition began in 2013. Marshall and other former residents were offered spaces in the replacement units before anyone else. About 100 accepted.

Today, roughly 715 units, some of which are scattered in the surrounding neighborhood, are under construction or have been completed. About 300 public housing units are in the original Iberville footprint. Offsite, a 17-story high-rise building, shuttered school buildings and a historic grocery have all been restored.

The $600 million total investment, funded through state, local and federal money, has contributed to other private investment totaling $4.4 billion, officials said. That includes renovation of the Jung Hotel on Canal Street, the extension of a streetcar down North Rampart Street and St. Claude Avenue, and the Lafitte Greenway, which cuts through the rear of Bienville, they said.

Another 227 of Bienville’s units are priced at market rate, with the average one-bedroom apartment renting for at least $1,095 a month, and two-bedroom units starting at $1,450.

Another 151 units are reserved for “workforce housing” and are priced at rates affordable to teachers, police officers and others who may earn more than public housing residents but who still need a subsidy to live near the Central Business District.

All residents have access to a computer learning center, an early childhood reading room, three fitness centers, parks and an outdoor dining area. The area is also home to two small businesses, Backatown Coffee Parlor and Magnolia Yoga Studio.

The amenities are intended to help lift residents out of the poverty that made them eligible for governmental assistance in the first place.

“What we are trying to do is get our residents to be self-sufficient, and so you are working on: What are the barriers that are preventing you from doing that?” said Kennedy.

HUD awarded only $4.5 million for that purpose. But Urban Strategies raised more than $20 million in private investments for social services. HANO also created a $500,000 endowment to keep those services going for the next decade.

The money pays for the team of case managers and workforce and education specialists who work to help connect residents to jobs. HRI, which also developed the Homewood Suites by Hilton hotel on Rampart Street near Bienville, worked with Urban Strategies on a hospitality training program for Bienville residents.

Overcoming obstacles

The project was not without its challenges. Though the 821 replacement units were supposed to be joined by more than 1,493 apartments, financial problems prompted HANO’s staff to reduce those goals.

“That original plan, you can throw it out the window,” Gregg Fortner, HANO’s former executive director, said in 2015.

Only 1,305 units associated with the project today are complete or under construction. About 715 of those are replacement units.

And there were other issues.

Early on in the project, construction vibrations threatened to damage historic tombs in the nearby St. Louis Cemetery.

Then a general contractor required to meet disadvantaged business enterprise participation requirements — Woodward Design+Build — was taken to task by HANO after two DBEs passed along the majority of their assigned work on Iberville to non-DBE firms.

The DBE controversy sparked policy revisions and training for contractors involved in the project, and the city also beefed up its own DBE policies to prevent similar situations.

Eight years after the grant award, HANO and its partners say the redevelopment has largely achieved HUD’s aims. The crime rate in the immediate vicinity of Bienville Basin has been cut by nearly a third, and 80% of low-income residents have seen “positive outcomes” after being assigned a case manager.

Marshall is among them. He’s working with his case manager to transition from a restaurant job to starting his own business, he said.

He sees his neighborhood, now dotted with new businesses and activity, as a bright spot downtown.

“It pretty much changed the whole area, because it’s not just focused on the development itself,” Marshall said. “It’s focused on the whole footprint.”